Psychological Habituation Theory

Habituation is the simpler form of non-associative learning that allows it to be efficient and not waste processing power (Groves & Thompson, 1970). Indeed, our brain needs to create some filters and barriers that block low-priority stimuli to avoid concentrating all our mental energy on something that is not important to allow us to adapt to the environment (Huron, 2013).

Groves and Thompson (1970) developed a dual process theory of response where the general assumption in the model is that every stimulus has two main properties, it evokes a response and influences the "state" of the organism. From the research on spinal neurophysiology, they theorized the existence of two processes that happen and evolved independently but interact to yield the final behavior of the organism (Groves & Thompson, 1970).

The first one, defined as habituation, which is high-stimulus specific, happens in the S-R pathway, the most direct route through the central nervous system that goes from stimulus to a discrete motor response. This inferred decremental process, which goes exponentially and then reaches an asymptotic level, occurs after the repetition of an effective stimulus (Groves & Thompson, 1970).

At the same time, the repetition of an effective stimulus creates an inferred incremental process, defined as sensitization. This happens in the state system, where the state is the level of excitation, arousal, and responsiveness of the organism (Groves & Thompson, 1970). This process happens because there are some “significant” stimuli with a positive reinforcement value that we do not habituate to, like pain and fear (Huron, 2013). This process of sensitization first grows and then decays; repeated presentation of a stimulus leads to progressively less sensitization (Groves & Thompson, 1970).

After the habituation process occurs, there are two ways to allow the organism to regain responsiveness. The first one, called spontaneous recovery, is the regain of responsiveness and re-sensitizing thanks to the passage of time. Leaving the organisms alone will lead to a complete response after the stimulus is presented again (Huron, 2013). The second one, called dishabituation, is the increase in the response after a strong or different stimulus is presented. This novel dishabituation stimulus disrupts or abolishes the process of habituation to the first stimulus (Huron, 2013).

They observed the hindlimb flexion reflex, in acute spinal cats, to study how the interaction and differences in stimulus variables (frequency and intensity) determine the final behaviour of the organism, through the two hypothetical processes of habituation and sensitization. They concluded that with low-intensity stimuli, the organism habituates more as the frequency increases. When intensity is higher, there is an increase in the hypothetical sensitization process with a decrease in the habituation one, with the same relation between intensity and frequency. When the intensity is high, for all frequencies, the process of sensitization prevails (Groves & Thompson, 1970). The sensitisation and habituation curves add together to form the actual behavioural response curve, in general, a U-shaped function of stimulus frequency and stimulus intensity (Groves & Thompson, 1970). The process of habituation will be faster as the stimulus presentations are more frequent, predictable, in higher numbers, less intense and it will be easier if there was a history of habituation in the past (Huron, 2013).

Bashinski et al. (1985) testing the dual process theory with 4-month-old infants, exposing them to complex and simple patterns, extended the applicability of Groves and Thompson’s theory, tested only for animal species, to the interpretation of infant visual attention. They stated that sensitization is influenced by stimulus complexity and not by stimulus intensity as previously formulated by Groves and Thompson. It is theorized that in the dishabituation process, the response to the familiarized pattern, after the introduction of a novel stimulus, depends on the magnitude of change and complexity of the novel stimulus, because complex patterns produced an increase in fixation (Bashinski et al., 1985).

The research by Kaplan and Werner (1986), through two experiments on infant visual fixation dynamics, tested Bashinski's hypothesis concluding that infant habituation functions are often nonmonotonic, with an initial increment in responding related to stimulus complexity, if the sensitization process prevails. Dishabituation, followed by decay, happens after the introduction of a complex stimulus, and not after a simple one. So the response of the organism to novelty is enhanced by the complexity of the novel test stimulus (Kaplan & Werner, 1986).

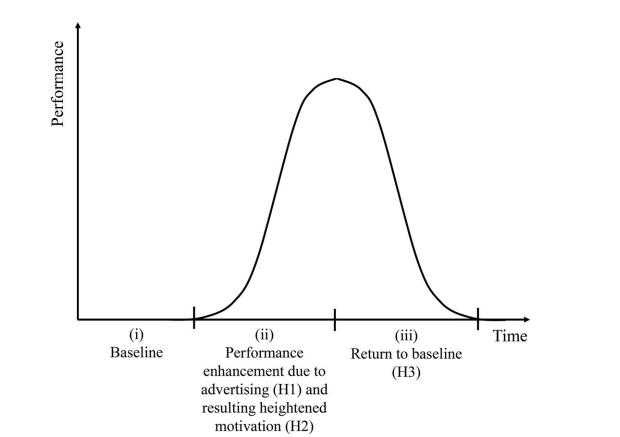

This theory's applications to advertisement are crucial because what distinguishes it from other messages is its highly repetitive nature as a way to get into customer's minds (Nan & Faber, 2004). The first evidence of the importance of continuous new advertising, that can contrast the brand to being forgotten, comes from Germann and Garvey (2022) that focused on the habituation of performance brands that promise their consumers to gain improved performance, just by wearing them. As shown by the figure 1 exposure to novel advertising, congruent with a performance-branded product in use, can drive efficacy expectations for improved performance. The performance enhancement effect does not last in time, because according to the psychological habituation theory products fade into the background. So as exposure frequency and duration of the brand advertisement increases, the salience of the advertisement decreases, leading to a decrease in performance due to less heightened motivation (Germann & Garvey, 2022).

Figure 1: Performance brand enhancement due to advertising (Germann & Garvey, 2022)

Another research in support of the importance of novelty in advertisement techniques by Karniouchina et al. (2011), showed an inverted U-shaped relationship between the year of the movie and the gain from product placement, demonstrating that with time people are becoming aware of the presence of product placement in movies and are more resistant to this tentative of persuasion.

The reason behind is that, when an information is already in the memory storage, the stimulus is not salient anymore, leading to less attention and no response to that (Portnoy & Marchionini, 2010). This can be a problem, as demonstrated by the experiment in which students were asked to ignore a door with a warning sign (Portnoy & Marchionini, 2010).

This lack of salience led the habituation process to be the main cause of losses of gains from online advertising (Portnoy & Marchionini, 2010). With time the online user notices fewer advertisements, compared to readers of journals, because they learned from the previous use of some websites, to recognise banners and automatically move the content of the webpage (Hsieh & Chen, 2011) just focusing their attention on what they need (Hsieh et al., 2012). Benway proposed the existence of Banner Blindness when testing the design and layout of banner ads and discovered that 80% of their subjects were not aware of these banners. He found out that, making the banner more visible and different from the webpage, can be even worse because it is more easily recognised as undesired information (Hsieh et al., 2012).

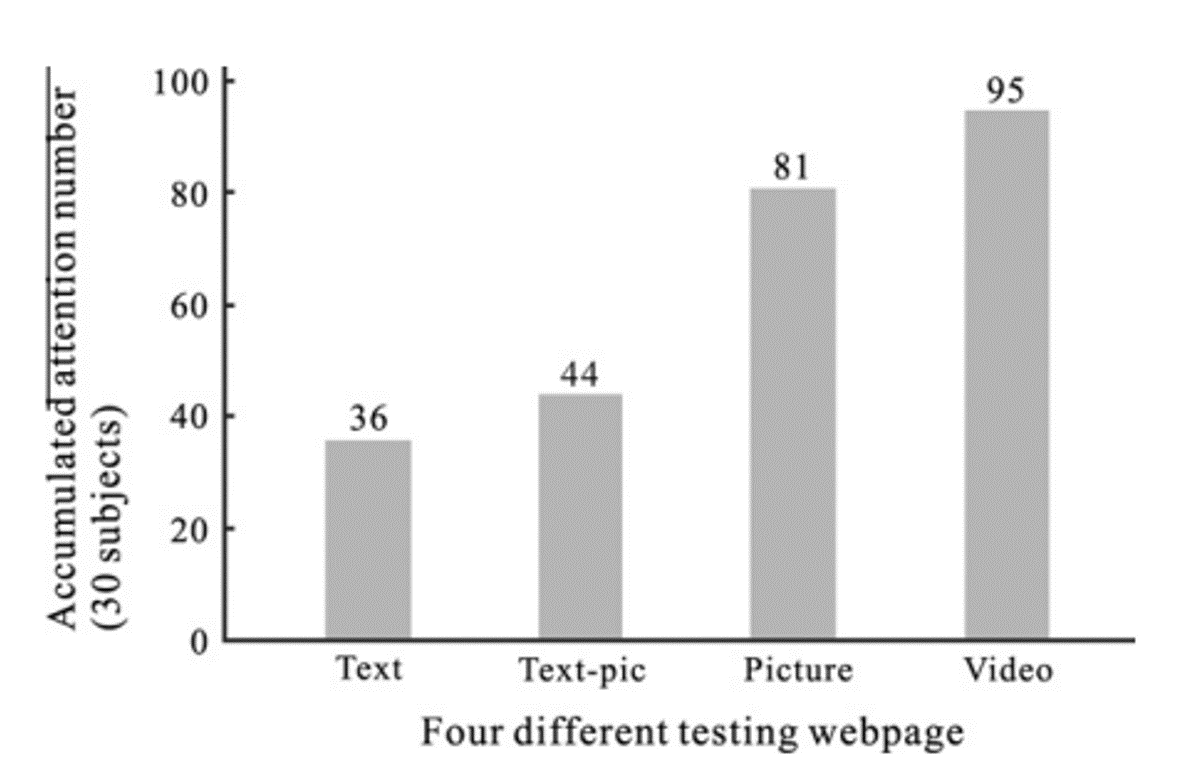

This study by Hsieh and Chen (2011) indicates that the attention of a user on a structural website can vary according to different types of web pages; with picture-based and video-based web pages slower in habituation compared to text and text-picture mixed information types, as shown in Figure 2. These differences are visible only on the first page, as the user can judge the banner as a distractor, the attention drops (Hsieh & Chen, 2011).

Figure 2: The accumulated attention number (Hsieh & Chen, 2011)

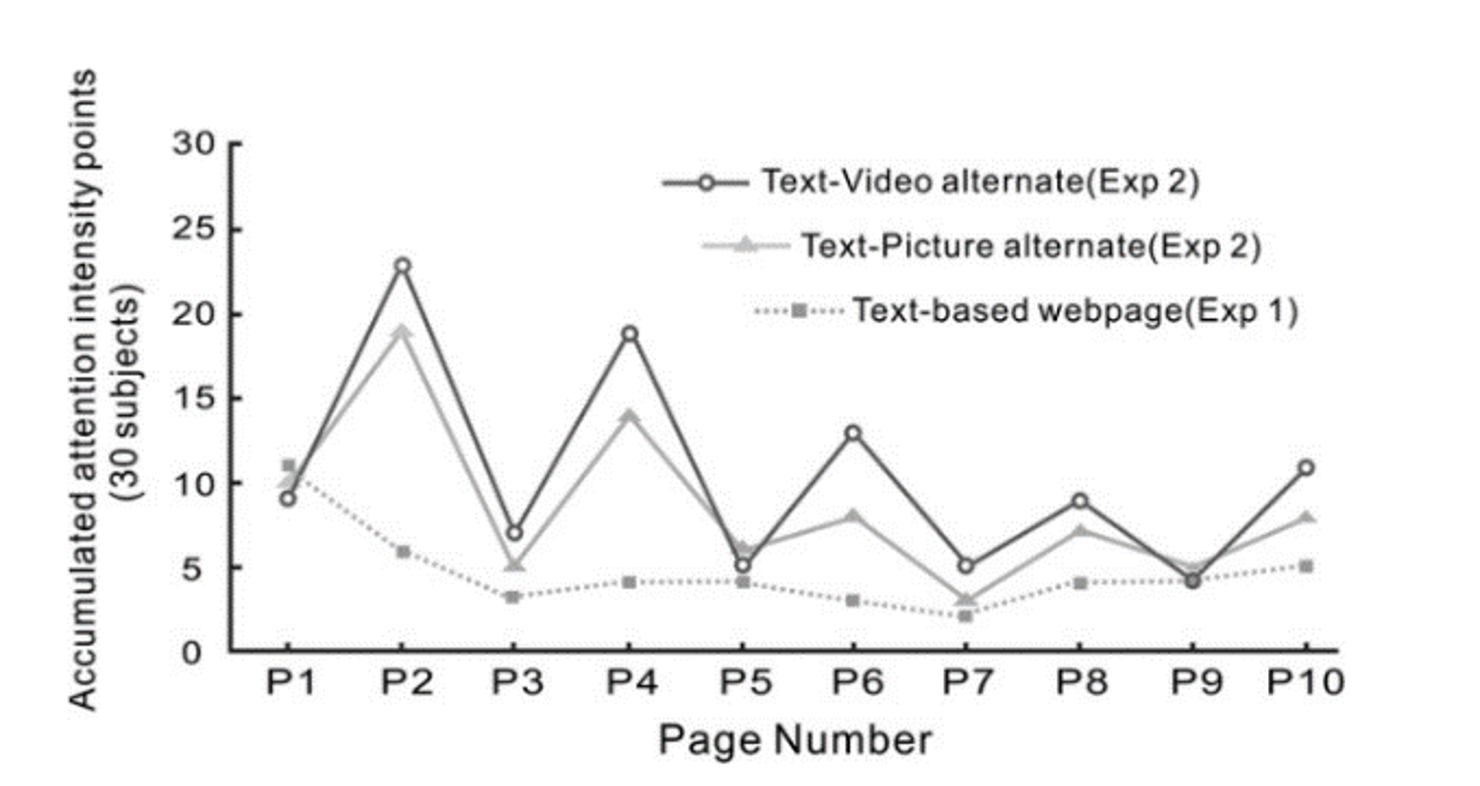

A further study by Hsieh et al., (2012), applying the theory of dishabituation, proposed a way to decrease banner blindness, demonstrating that it is possible to keep viewer attention on banners on subsequent pages with some stimulus variation, through the alternation of information types in a sequence of web pages. They changed the design to a two-page 2 information type cycle so, as the user goes through subsequent pages, novel stimuli catch his attention, drive interest in the content and he needs more time to recognize and acquire the new design (Hsieh et al., 2012). This effect does not last in time because after a lot of repetition the new design is integrated into the pattern of repetition and the attention drops again, as it is visible in Figure 3 (Hsieh et al., 2012).

Figure 3: Accumulated attention intensity points for each webpage (Hsieh et al., 2012)

All this research demonstrates that an advertising to be valid, should be new to drive interest and not too repetitive, otherwise attention and revenues from that will drop, due to the Psychological Habituation Theory.